outcomes by targeting the genetic material of viruses directly [10]. However, realizing the full potential of these therapies requires overcoming significant hurdles related to delivery systems, specificity, immune evasion, and the cost of therapy.

This review seeks to delve into the recent developments and current state of nucleic acid therapeutics in the context of viral infections. It aims to synthesize insights from various research studies and clinical trials that have highlighted both the successes and the ongoing challenges faced by these therapeutic strategies [3, 11]. Furthermore, the review will critically analyze the mechanisms of action of these therapies, their efficacy and safety profiles, and the innovative strategies being developed to enhance their delivery and precision. By providing a comprehensive overview of nucleic acid therapeutics, this review will contribute to the broader understanding of their potential impact on the field of antiviral treatment and will outline the necessary steps forward to address the existing research gaps and clinical challenges.

Types of nucleic acid therapeutics

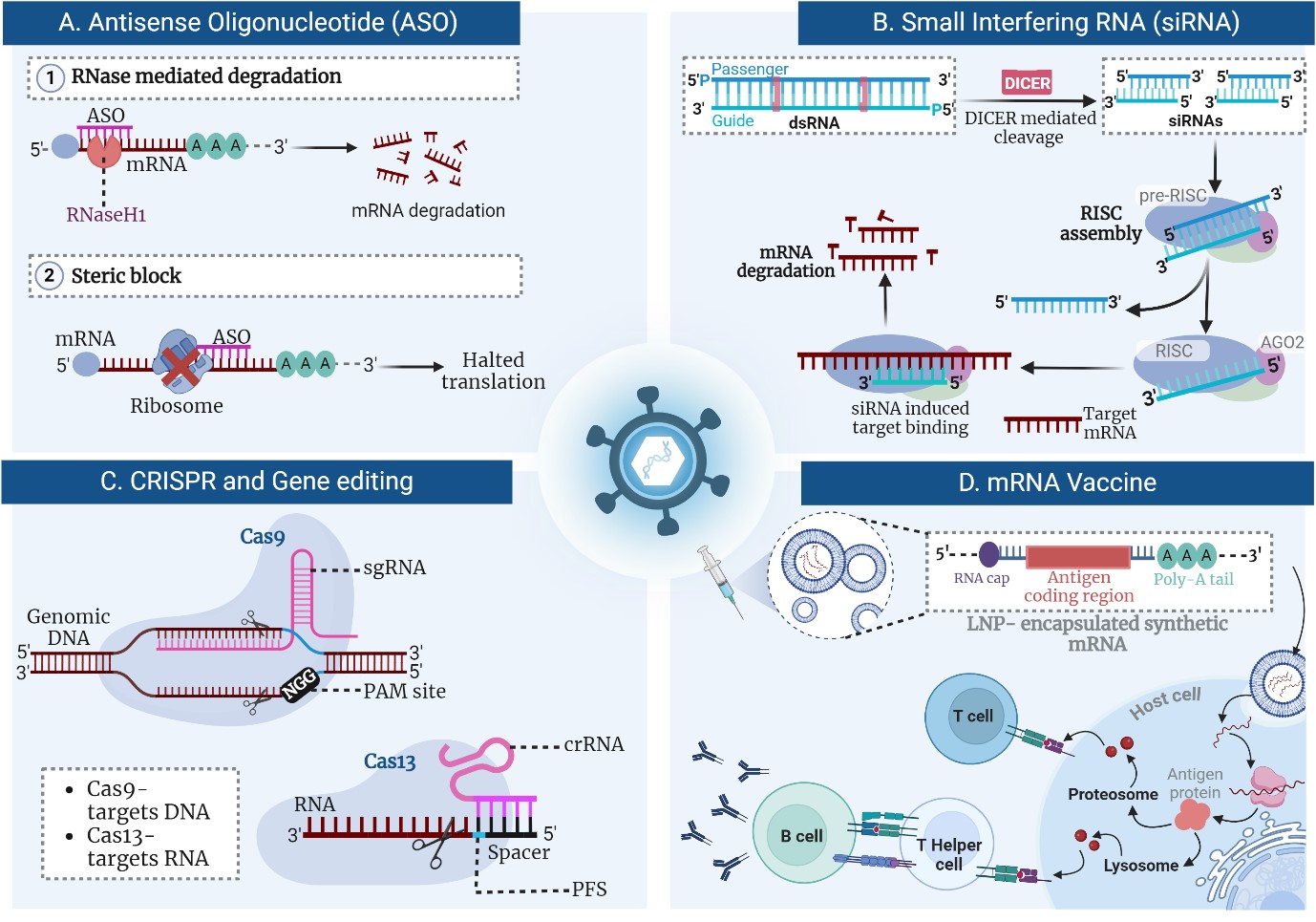

Antisense oligonucleotides

ASOs function by exploiting the natural cellular mechanisms of gene expression regulation, providing a precise method to modulate genetic outputs. These synthetic, single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules are designed to be complementary to specific mRNA sequences of interest [12]. Upon administration, ASOs hybridize to their target mRNA through Watson-Crick base pairing, forming DNA-RNA or RNA-RNA duplexes (Figure 1A) [13]. This binding can lead to one of several outcomes depending on the ASO design and target sequence. One primary mechanism involves the recruitment of RNase H, an endogenous enzyme. When an ASO binds to mRNA, it forms a hybrid duplex that RNase H recognizes and cleaves the mRNA component of the duplex. This enzymatic cleavage leads to mRNA degradation, effectively reducing the translation of the target protein [14]. Another mechanism by which ASOs exert their effects is by steric blocking. Here, the ASO binds to mRNA but does not lead to its degradation [15]. Instead, it physically obstructs the translation machinery or the processing of pre-mRNA, thereby preventing the synthesis of the protein. This method is useful for modulating processes such as splicing, where the ASO can alter splice site selection to promote or inhibit the inclusion of specific exons in the mature mRNA [16]. Additionally, ASOs can be modified to enhance their stability, cellular uptake, and binding affinity. Modifications such as Locked Nucleic Acids (LNAs) and phosphorothioate backbones are common, helping to protect ASOs from nucleases and improve their pharmacokinetic properties [17]. This allows for more effective and sustained gene silencing with potential applications across a range of diseases, from viral infections to genetic disorders. Through these diverse mechanisms, ASOs provide a versatile platform for therapeutic gene regulation, allowing for the targeted silencing of detrimental genes with high specificity and minimal off-target effects [18]. This targeted approach is especially significant in the field of antiviral therapies, where precision and adaptability to rapidly mutating viruses are crucial. Research by Dauksaite et al. showcases the utilization of locked nucleic acid gapmers, a type of ASO, to target the RNA genome of SARS-CoV-2, achieving a significant reduction in viral load in vitro by up to 96% [19]. Similarly, Lu et al. developed ACE2-specific ASOs to reduce SARS-CoV-2 infection rates by downregulating ACE2 expression, a critical receptor for the virus, demonstrating potent in vitro and in vivo efficacy [3]. The clinical trial outcomes, though preliminary, have shown promising results, necessitating further studies to establish long-term efficacy and safety profiles [20, 21]. Collectively, these advances underscore the transformative potential of ASOs in providing a new arsenal against viral pathogens, paving the way for broader applications in infectious disease management.

Small Interfering RNA

siRNA operates through a sophisticated cellular mechanism known as RNA Interference (RNAi), which plays a crucial role in gene regulation and antiviral defense. This process begins when double-stranded RNA molecules are cleaved into short 21-23 nucleotide siRNA duplexes by the enzyme Dicer (Figure 1B) [4]. Each siRNA duplex consists of a sense strand and an antisense strand, the latter of which is essential for the mechanism's specificity. The antisense strand of the siRNA is then incorporated into the RNA-induced Silencing Complex (RISC) [22]. The RISC is an assembly of proteins that facilitates the interaction between siRNA and its target mRNA. The siRNA serves as a guide for RISC, directing it to a complementary sequence on the mRNA transcript. Upon binding, the Argonaute protein within RISC utilizes its endonuclease activity to cleave the mRNA,