education, and life expectancy [2]. Approximately 40% of Afghans did not make enough money to meet their basic requirements, such as food, and were therefore living in poverty in 2013–2014 [1]. Consequently, many Afghans, notably the 16% of the population under five (whose nutrition, growth, and development determine the country's development and prosperity opportunities), are at risk of food and nutrition insecurity due to conflict and economic downturn [3]. Consequently, the rate of child stunting continues to be intolerably high, with 20% of children under five years old suffering from severe stunting and 40% having stunted growth [4]. Moreover, since 2004, the child wasting rate has been constant at 10% [5,6] This indicates that most children and infants in Afghanistan do not get adequate nutrition.

Suboptimal eating results in child and infant mortality. Notably, the mortality rate of children and infants among children under five in Afghanistan is mediated by low nutritional status as well as diseases such as pneumonia and diarrhoea, among others. Moreover, breastfeeding status is one of the highly significant causes of neonatal and child deaths in Afghanistan [7,8]. The current statistics have shown that only 43% of Afghan newborns aged 0-5 months receive breast milk [1,3]. More alarming are the complementary feeding practices whereby only 16 percent of infants aged 6 to 23 months receive meals that meet the required minimal frequency and variety of feedings [1]. This calls for considering young infants' nutritional needs, especially those of breastfeeding age, in this country.

Several studies have suggested that the level of breastfeeding among the women of Afghanistan is influenced by certain factors based on demography. For instance, according to the statistics collected in the 2015 Demographic and Health Survey, child-feeding practices in Afghanistan vary from one region of the country to another. Another finding from the work conducted was that the wealth index was a significant determinant of the optimal breastfeeding practices in households with lower levels of wealth index who seemed to practice poor breastfeeding practices compared to those with higher wealth index [3]. Likewise, the gender of the baby affects South Asian women’s breastfeeding habits, where girls are exclusively breastfed more than boys [9]. Similarly, a cross-sectional study involving participants from five South Asian countries, including Afghanistan, conducted by Hossain and Mihrshahi (2024) [10], established that raising maternal education of the mother had different positive effects on breastfeeding. This infers that the mother's education level could influence Afghan women's breastfeeding habits. However, there is a limited number of empirical and recent studies that have examined the factors influencing breastfeeding practice among women of reproductive age in Afghanistan, which in turn points to a literature gap. Therefore, this study seeks to address this gap by assessing how women's breastfeeding practices in Afghanistan are influenced by demographic factors, including geographical location (provinces), wealth index, gender of the baby, and the mother’s education level.

Methods

Data source and study variables

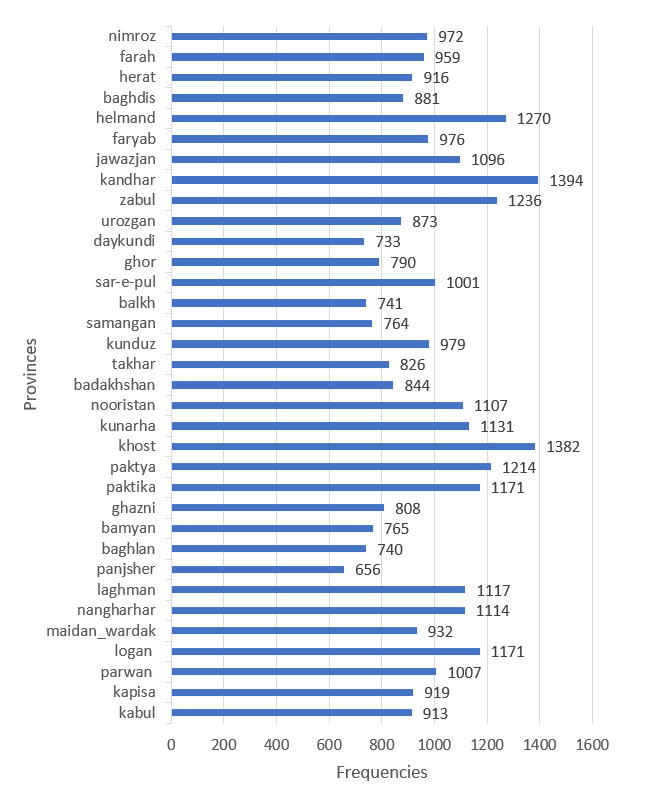

The study used data from outside websites, i.e., the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) (2022-2023). This survey was carried out in Afghanistan as a part of a global MICS survey by the UNICEF Afghanistan Country Office in partnership with the National Statistics and Information Authority, with funding from the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund and World Bank Group. The data was collected using four types of questionnaires i:e, households, women, children under five and children aged 5-17. The data is collected from the end of September 2022 to 28 February 2023. For this research, only children under-5 data is used, which is filled by the mothers or caretakers of all the children under the age of five years living in the house. The sample includes 33,398 children and 32,989 Mothers or caretakers with a 98.8 per cent response rate-the 2019 NSIA Sampling frame using satellite imagery. The structure is based on the MICS6 standard questionnaires and customized into local languages "Pashto" and "Dari" from the standard English Model.

Variables and data analysis

There are two types of variables used in this study, and they are:

Dependent: The outcome variable is whether the child has ever been breastfed, classified as yes coded as one and no Coded as 2. Yes, it is for those children who have ever been breastfed, while no is for those who have never been breastfed.